Art. Art is a prickly subject: a definition of art is worthless to anyone other than the person who has made the definition, and even if something is widely considered art, deciding whether it is to be considered GOOD ART or BAD ART is another layer of subjective bullshit wrapped around an already directionless and ultimately endless discussion.

Which is good, because one thing I’m not here to do is tell you whether games are art or not, because frankly I don’t really know how I think about it and I really don’t think coming to a conclusion on that would help this article.

What I want to talk about is games media, and more specifically its reaction to one particular scene in what is likely to be the biggest game of this year (if not this console generation), Grand Theft Auto V, and how that reaction is regressive and problematic when contrasted with what the aforementioned media seems to want to focus upon.

NOTICE: THIS ARTICLE CONTAINS STORY SPOILERS FOR GRAND THEFT AUTO V. CLOSE THIS WINDOW IF YOU DON’T WANT THE STORY SPOILED FOR YOU. BECAUSE THE STORY WILL BE SPOILED IN THIS ARTICLE.

IT ALSO CONTAINS GENUINELY DISTRESSING IMAGES.

SURE ABOUT THIS?

LAST CHANCE, PILGRIM.

FINE.

Anyone who has played one of the 3D Grand Theft Auto games will probably have a rough idea of what takes place in the latest instalment of the franchise. Don’t get me wrong, there is plenty that’s new and different in GTA V compared to its older siblings, but the central theme is still “cut about a city doing whatever you like, but if you choose to follow the story you’ll be committing crime”. The biggest change to the game is the player’s ability to switch between one of three characters pretty much at any time, progressing each character’s story at different rates (and doing an incredible job of subtly encouraging roleplaying, but that’s for another article).

One of the characters you can choose to play as is a man called Trevor: a dangerous, aggressive and unpredictable scumbag who has spent the last ten years or so under the impression that his friend Michael (another playable character) is dead. He’s ex-forces, an ex-bank robber and quite possibly the most psychotic character in any Grand Theft Auto game (as seen when Johnny Klebitz from GTA IV: The Lost and The Damned is absolutely obliterated by him in the opening seconds of his introductory cutscene).

Anyway. A few hours into the game the gang of characters the player has control over finds themselves caught up with a bunch of corrupt government officials from the game’s equivalent of the FBI and CIA. Real bad news dudes – and one mission sees you breaking into a building to take a young immigrant man into their custody, as they believe he may have information that would be useful to them.

Of course, the man swears he knows nothing. He says he doesn’t have a clue about the things he’s being asked about. The trouble is these FBI and CIA agents don’t believe him, so they call in the baddest man they know to get the information from him. What follows is a torture scene in which the player controls Trevor, choosing which torture implement to use on the captive, before using the chosen tool on the man in order to persuade him to cough up the desired information.

This mission has caused some controversy in the video games media. It’s popped the ignorant, hands-over-ears bubble that the vast majority of the industry floats through the world inside. This is a media that goes to incredible pains to point out that video games aren’t just for children any more; a media that is constantly trying to find its Citizen Kane, even if a) half of them don’t really know what that means, and b) the idea of a single work in a medium suddenly becoming the fulcrum that propels everything within it to being considered art is, frankly, laughable.

Games media is constantly trying to legitimise the hobby it’s built on: to prove that games can be every bit as valid as movies and art and novels. But for some reason, rather than celebrating titles that claw at the boundaries of what is accepted, the media’s first response when presented with something difficult is to turn its nose up in disgust and claim that it’s damaging the medium.

This is dangerous, regressive bullshit that will do the games industry no favours.

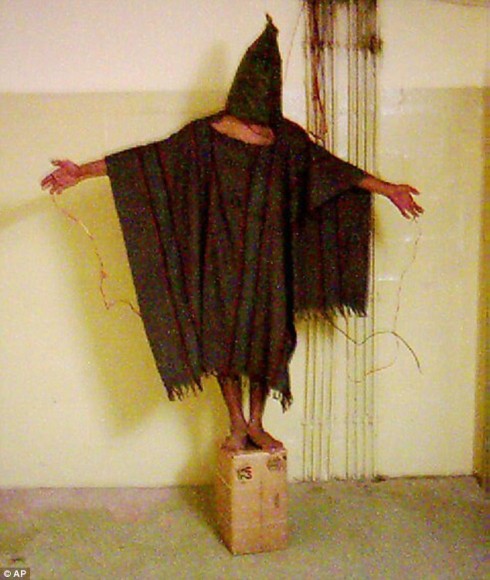

Some complained that the mission makes no sense in context with the story; why would this team of corrupt law enforcement officials go out of their way to rescue this man, only to then torture him? It simply doesn’t make sense, they say. I’d like those people to look at the images linked to here, (CAUTION: CONTAINS GRAPHIC, UPSETTING IMAGES). I have reproduced the most famous (and arguably least shocking) below:

None of these images make sense. The smiling faces of the American soldiers standing over (or sitting on) prone, bound men and women make no sense in any context whatsoever. The fact that many of these people were kept in these conditions for days or weeks is ridiculous; those are representatives of American justice and freedom containing these people; people that the West are supposed to fear – and yet seem so pathetic when they’re hooded and bound in a corner.

Whether what GTA V presents is a grim satire or not begs to be discussed, but to me the fact that three corrupt American law enforcers chose to interrogate an immigrant in this way seems entirely logical – and the fact that the scene is difficult to watch (and partake in) should be celebrated as one of the few moments where video games take a step towards genuine maturity and actually force us to do something other than step into the shoes of the morally just hero who either only kills “baddies” or can be absolved of all sins because of some wider, grander goal. The game is forcing you to be abhorrent and unpleasant, and gaming society turning its head in disgust at this only serves to demonstrate that it simply isn’t ready to be taken as seriously as it demands.

Taken in a broader context as part of Trevor’s character arc, this mission is also one of the most important in the game’s narrative. Trevor is a ticking timebomb and nobody knows this like Michael does. As you alternate between controlling the two characters Michael repeatedly tells a CIA agent accompanying him just how dangerous his former partner in crime is; how he does not listen to reason, how he does not listen to authority, and how little respect he has for those who fall outside of his twisted (but strict) moral code. People have complained that Trevor driving his victim to the airport is a weak attempt to try and make amends for what he’s just done, but I don’t believe that for a second: what we are seeing is a demonstration of Trevor’s morals in action. He may have done something awful for money, but by helping the man flee the country the game is trying to show us how much contempt he has for authority.

Later Trevor commits further awful deeds (some of which are optional, some not) that truly mark him out as something dangerous – and at the end of the game, if the God of the digital world in which he lives deems it necessary, he can be put down, like a dog that can’t be trusted around people.

The game lacks a single, central antagonist (at least in the common sense) and instead asks the player to decide whether this man, who has committed atrocity after atrocity (as well as being responsible for some of the game’s funniest and more touching moments), many of which the player has been implicit in, is in fact the “big bad” that has to die at the end of every video game. It’s making you play both Antagonist and Protagonist in one character, then making you decide his fate.

If Trevor has disgusted you from start to finish then he’s achieved something that no other video game final boss has, and deserves his place in the history books as one of gaming’s most interesting characters. This is new territory for games, and by simply dismissing the whole game because of a single scene the media around it is robbing itself of the opportunity to make an informed decision about the game, as well as highlighting itself as a medium whose critical apparatus does not yet deserve the type of attention it craves.

Some have discussed player agency as a factor in the torture scene, and the fact that they were involved in the deeds making it worse. That this is perceived as a problem is, to my mind at least, worrying when coming from the mouths and keyboards of those who are involved in writing about video games. Agency is what makes this platform unique. Film critics don’t complain about violence because they can see it, nor do music critics complain about disturbing albums because of the unpleasant sounds they hear. When you insert a Grand Theft Auto disc into your console, you should not be surprised when the game asks you to do something dreadful. Interestingly those same folk who complain about being complicit in the torture scene rarely complain about the slaughter they committed in an attempt to retrieve a briefcase of money, or the man they shot dead so they could give his golfclub to a pensioner.

Agency and control over the world is the one unique thing we have in video games, and complaining about doing cruel, violent things in Grand Theft Auto is like filling your mouth with super-sour sweets then complaining that you can taste them.

Art. Art is a prickly subject, but if video games are ever to be considered art – nay, if the discussion as to whether or not video games could be considered art is even to be taken seriously – then its audience and its critics need to adapt. Some of the most fascinating and world-changing pieces of literature, film and music have been the most challenging for their audiences – they push boundaries and force us to question our own internal beliefs and morals – and if games are ever to be considered to offer more than a comforting story for children in which the hero gets the girl and the prize at the end of the tale, then those writing about the medium need to start treating it as such.

Comments

5 responses to “If You Want to be an Adult, Stop Acting Like a Child”

The bulk of mainstream games clothe themselves in violence: so far, it's been largely for the force of good. There are some shades of grey but we've got these three archetypes, with some mix-and-match available to players: hero who kills righteously (Gordon Freeman), amoral anti-hero who does what he has to do (Joel, The Last of Us) or Rorschach, a psychopath (Trevor). There are plenty of other ways to have "unlikeable" player-characters, but crafting psychopaths seems a bit extreme, a Michael Bay reaction to "we need higher art".

I've played Beautiful Escape – a psychopath simulator – which is incredible. If you have the stomach for it, I think this is one of the best games to come out in recent years. It can turn the stomach of many a player and is just… clever. The problem with GTA: Torture Edition is the frame; it's very much the fun, riotous, let's-have-a-jaunt flavour of game. We're slowly coming out of our post-911 haze of torture-is-just-because-the-good-guys-are-doing-it and having an enforced torture sequence seems really incongruous in a game about fun. Players aren't questioning shooting people in the face, they're not questioning running over pedestrians – I can't see why GTA V is the best vehicle for considering torture.

So I'm not saying torture shouldn't be in games: but I don't if it fits a GTA title at all.

Caveat 1: I haven't played GTA V, so I'm doing Devil's Advocate here!

Caveat 2: You're a prick. (I saw your tweet last night =) )

Funnily enough I was thinking about Beautiful Escape as I was re-reading this.

I can see your point regarding the context in which the scene is placed, but I don't think that section was put in there to make some political point – I just think it was put in there as an example of the way that criminals get information out of people that won't give them the information willingly.

My main complaint was with the way many writers immediately wrote it off because it challenged their morals (like the rest of the game isn't morally challenging as it is), without understanding the scene as a part of a bigger arc. Trevor is genuinely dislikeable; a violent and dangerous man who does a lot of things I didn't like – and you can kill him at the end. I read so many pieces saying they'd given up on the game at the torture mission and that it was icky and they didn't like it – while there are films and books out there that are more challenging, upsetting and difficult to read – but they're often praised for pushing the boundaries of the viewer/reader, not criticised for being mean.

Something I would contest in your examples is that I think Joel has a more interesting arc that, for me, blurred the lines between someone you empathise with and someone who is something of a straight up selfish monster or psychopath. I like how there is a lot of grey area with his character and there are moment, especially the end of the game, where a lot of his actions are indefensible. Also, the sections where he is separated from Ellie are incredibly revealing and add a whole new layer to his character. Incidentally, one of his Ellie-free scene sees him torturing folk with absolutely no moral qualms.

The GTAV torture mission has a larger point to make, and my first criticism of it would be that it's incredibly unsubtle in delivering its message; the scene flits between Trevor torturing the victim and Michael using the what is clearly mostly made up information to single out a target at a party. He reveals that the target is Azerbaijani, and part of the joke is that none of them have the slightest clue what an Azerbaijani man looks like. There are various other anti-torture opinions spoken out loud by Trevor and the victim, and it's all very much route one, in your face SATIRE.

From this, my criticism of games writers who didn't get that is that I am stunned that they missed the incredibly heavy-handed point the game was trying to make. It shows a lack of ability to apply even the most basic analysis to the scene, and presumably their knee jerked so hard it hit them in the chin, rendering them unconscious for the remainder of the mission.

GTAV hits a tone of big crime movie – people felt San Andreas was too silly, people felt IV was too serious and bleak, putting it at odds with the nature of the gameplay. GTAV hits the tone that fits the gameplay better than it ever has, with larger than life characters that you are intended to enjoy as such, whilst occasionally making satirical points (albeit in a very basic fashion).

Trevor Philips is Patrick Bateman, a man so cartoonishly psychopathic that you almost wonder whether he is real; a theory backed up by the wildly unrealistic car chase scene. I'm not saying they've written a story as deep as American Psycho – far from it – but Trevor is meant to be a ludicrous extreme of a character, a horrible, frightening character who still manages to occasionally make you laugh in spite of yourself (something American Psycho also achieves) and you find yourself ever so slightly, just the tiiiniest bit, identifying with him. He is one of my favourite videogame characters this year.

You can find it unpleasant, distasteful even, and be turned off by those things – that's fine – but I don't think you can or should denounce the entire game on such a comparatively small element of the game as a whole.

(Sorry if that was a bit rambling, I wrote it in three bits over about three hours)

I've just gotten around to reading this and really enjoy how this is a point of view (on a more general scale, since I haven't played GTA V yet) that I've never really considered, having been sitting more on the side of the general bulk of the games journalists and players who are all too quick to dismiss video games depicting violence as uncreative and harmful towards the image of gaming culture.

While I think that's still true in a majority of cases, and that violence is video games is very frequently an over-milked and abused cash cow for a lot of publishers, you do raise a particularly valid point that it can be done in an interesting way that challenges the player/viewer – and if literature and movies can be congratulated for that, then games certainly should be too.

Writing this comment has actually made me think of the somewhat unrelated gameplay of Defcon, which I think can achieve a similar sort of response from players and deals with a similar narrative in a much more abstract way.

[…] wrote about the benchmark Trevor moment, which is him torturing an innocent man. Spann argued that this scene was important due to gaming […]