It’s now been a solid eight weeks since the release of Christine Love’s latest indie game, Don’t take it personally, babe, it just ain’t your story. For a while it was the talk of the gaming blogosphere and no doubt you’re already at least aware of it. More likely you’ve played it, or read enough about it that you can pretty much recount the salient details without having actually clicked the mouse through it yourself.

So I shan’t waste time on introductions. Instead I’m going to talk a little about my personal responses to the game, and also go at it a little deeper than usual, with a bit more of a critical hat on. It’s the sort of game that demands such an approach. So if you do want to play the game, and you haven’t yet, then please don’t read any further until you’ve done so.

Here’s a short buffer paragraph to save prying eyes from stumbling onto an enormous spoiler: I found the story of DTIPB thoroughly engaging and quickly became invested in its various characters. Isn’t that nice?

Okay, now that that’s out of the way, here’s something else I want to get off my chest: Isabella, or more specifically, why the fuck do I keep falling for this shit? Isabella, for those reading with no intention of playing the game, is a student who disappears from the school overnight after missing a post-school meeting with you. The game suggests that she has committed suicide – the signs were present – and upon discovering this I was a little distraught, angry that I’d somehow failed to help her – the only challenge that the game was setting before me was helping those students who came to me for help. But, as it turns out, the suicide is an elaborate hoax – and there’s nothing you can do to stop Isabella missing your meeting. It’s a deliberate void placed in the game’s structure to both inculcate a sense of loss and failure, and to provide an essential ingredient in the narrative’s culmination. In other words, it’s another Garrus’ scar (I wrote the linked blog post before discovering that event was a narrative inevitability and never within my control; the subsequent sense of betrayal was directly proportional to how affecting I found it).

Of course, this is unavoidable, and in a novel I’d not have blinked at the deceit. It’s only because this occurred within the videogame medium – even one as limited in interactivity as this one – that I felt this sense of betrayal. Was it just me?

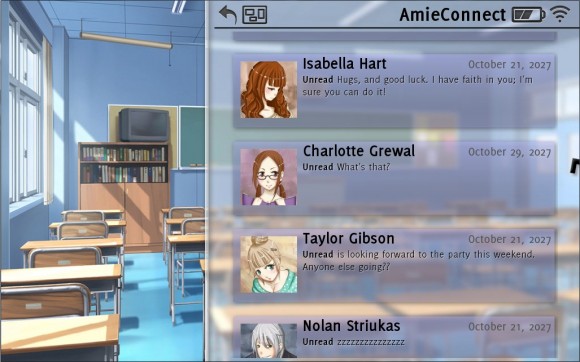

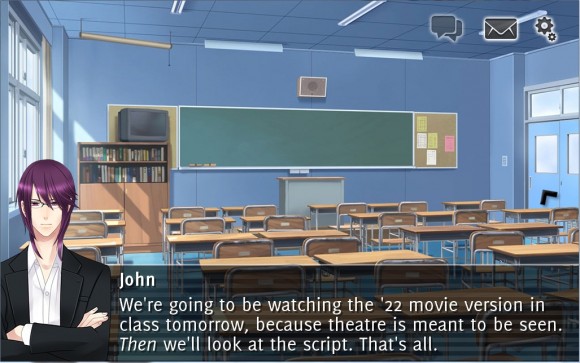

A deeper criticism: the game is thematically predicated upon the player – or at least the character of John Rook – being unable to resist prying into his students’ lives through the use of the Amie messaging system. However, this is never a real choice – even if the player opts to avoid it, the game will at points oblige them to do so. I’ve not tested whether it’s necessary to only read certain messages in order to proceed, but even if that were true: how would you know? This somewhat undercuts the theme of intrusion into personal privacy, because it’s an inevitable yet false choice.

Similarly, you’re obliged to read the 12channel pieces, which I like as thematic foreshadowing (ala. Japanese shadow puppet theatre, apparently, though I’m not too much of a wank hat-wearer to admit I’ve never heard of that before), but sometimes I’d have rather read them a bit later. Returning to the question of Isabella, I was in a rush to go and see her because I was worried and wanted to get to her quickly. Having later fallen for the hoax of her death, I found myself actually angry at the game for failing to offer me the choice to rush to our meeting. Obviously, in retrospect, I couldn’t have helped – but again I was betrayed by the game, albeit this time in a more immediately obvious sense.

Although Iz’s ‘death’ does lend the game a more sombre overtone that – if you’re invested in the fiction – makes you think more carefully about your later choices, I now wonder how much impact your efforts to ‘help’ actually have. On a second playthrough I selected a few of the less helpful options when I spoke with Nolan, and his plot arc alongside Akira was apparently unaltered. The unfolding affair, or lack of, between Rook and Arianna is a bit more varied: on my first playthrough I refused her advances, and in my second I grudgingly invited them, and I appreciated the different scenes and Amie threads the game presented as a result. Similarly, you ultimately control whether or not Charlotte and Kendall get back together. As far as I can tell, though, that’s it: two character arcs within your control, two without it.

I feel that a lot of the game’s effect comes from the illusion of choice and of power rather than its actuality. I feel that I could accept or even make the argument that this is what it’s really about – John Rook is a terrible teacher and few teachers have very much direct effect on their pupils’ lives, after all, and the theme of intrusion into privacy is not only a storyline fake-out – the pupils all know and even utilise this fact to their own ends, so unconcerned by it are they – it’s also a fake-out in terms of gameplay mechanics because you don’t really have that choice. But if I were to follow this argument to its logical conclusion I’d probably arrive at some sort of repugnant fatalism; let other people get on with their lives and don’t try to help as you won’t have any real impact. Don’t try to push yourself because you can’t beat your own limitations. Don’t grapple with the ethical quandaries that are part of your dayjob: accept the instiutional, social and technological framework around you because you’ve no choice but to do so. Take advantage of things you want to because, well, what else can you do? It’s a deeply depressing conclusion to arrive at and not one I feel the game is pushing you towards. And the students do come to you, after all, partly because they genuinely want your help, and partly because although you don’t realise this at the time, they know that you are privy to information they’re not thanks to your monitoring of the Amie network.

Having written all of this, I’m a little disappointed that I chose to revisit the game in the name of criticism. It’s something I’d recommend people only play once – or even avoid reading about – because to peep behind the curtain is to see an affecting, emotionally-engaging and well-written game revealed as a fairly linear and inflexible experience. Without the illusion of engagement it’s just a moderately well-written manga with a thematic reveal that is perfectly in-sync with the generation that’s grown up with social networking and the erosion of traditional notions of privacy. It’s a game very much of this time, these moments, and it should be experienced as such. For those of us who like to pull things apart and see how they work it’s also an engaging experience, but on a less profound and far more banal level.

If you want some further reading on DTIPB, I recommend checking Electron Dance, where a bunch of stuff was said that pretty much says it all. Alec over at RPS has some interesting thoughts as well. And for balance, here’s something I don’t agree with.

One final thought that I couldn’t work into the above piece: Kendall can show up Rook, if not in knowledge of then at least in analysis of some of the texts. A self-styled otaku anime nerd, her obsessive consumption of Japanese media seems to have given her a better grasp of narrative and thematic convention than whatever teacher training Rook was given. This revelation led me to think a little more about the conversations on 12channel which, lulziness aside, actually demonstrate a bit more analysis and understanding than you might expect from a bunch of 15-yr olds (if you weren’t, you know, 15 or whatever – teens shouldn’t be underestimated). Yeah, kids of the internet age can learn all sorts of shit because of the ease of access to works of fiction and mediums and information and message boards and debate and argument. They’re not achievers in school so you assume they’re not smart but you’re approaching it from the wrong end there; they’re just not engaged. You can engage just about anyone if you find something that interests them, and most people are smart enough to learn from that kind of experience. So, perhaps DTIPB not only tries to show that Rook’s ideas of privacy are outdated (with Rook here standing in for those of us older than 25; today’s younger generations grew up with mobiles and CCTV and electronic databases and youth ID and social networking and their world is not like ours), it also shows that his ideas about learning are antiquated. And that thought may be a lot more interesting and relevant today than the game’s overt discussions of privacy.

Comments

2 responses to “Don’t take it personally, babe, I only just got round to writing about you”

Ah, the nature of reviewing. It sounds like your second playthrough almost destroyed the experience for you. That first play is great – it makes you feel involved, if not completely immersed due to Rook's unappealing character – if just a little too long. I knew when I reached the end of the game that it was not possible to "save" Isabella as the whole game had relied on it, although was upset when she just disappeared and no one batted an eyelid at her loss – that just felt sad and ugly.

Incidentally, did you know you could "undo" your actions? I think it was something like backspace. I'd chosen the wrong option by accident in the earlier Arianna setpieces and I did NOT want to be in a relationship. Thank God I found the undo key and could play the game as I had intended.

There are so many things you can write about DTIPB which is why I just stuck with the privacy angle. But I think the most important thing, aside from all the naysayers, is this. Few people are writing modern, relevant games like DTIPB. Agency be damned: how many other games achieve this level of social context?

Hmm, there was a bit of an outpouring on Isabella's AmieConnect profile, but that was all. I put it down to kids not wanting to engage too closely with the death of a friend rather than not caring about loss, but can see why you felt as you did.

I had no idea about the undo button! I wish I'd known about that… well, actually, maybe it's best that I didn't. I am one of those people who used to stick his fingers into choose your own adventure books so he could go back if he made a mistake. Best that I was forced to stick with my chosen course…

The second playthrough did ruin a lot of what I liked most about the experience. Equally it allowed me to actually flesh out some of the more interesting ideas I had about the game (or at least, I hope they were interesting). I think it's just such a rare thing for a game to engage me emotionally and intellectually that I was upset when I found out that the emotional engagement was, in part, a hoax. But as you say, few games feel as /relevant/ to the world we live in as DTIPB does, and for that reason alone I'm glad I played it not just once but twice.