Today’s guest post is from cultural critic Jonathan McCalmont, who you may recognise from his video games column Blasphemous Geometries at Futurismic or from his extensive writing on a multitude of topics elsewhere.

Why the original X-Com is a classic…

I first played UFO: Enemy Unknown (or X-Com: UFO Defense as it was known in North America) in the mid-1990s on an Amiga 1500 that had seen better days. I played the game on a series of 3.5†floppy discs that would grind and spin as the computer’s limited computational power struggled to cope with the game’s isometric 3D environments. More prone to bugs and hangings than 1950s Alabama, the fight scenes were frustrating affairs that somehow kept me on the edge of my seat despite their chronic lack of pace. Here was a game that was doing something new, even if it was not doing it particularly well. However, what that game was actually doing only became clear to me once it was re-released on the original Playstation.

UFO presented itself as a hybrid of strategy game and 8-bit dungeon crawler; Pools of Radiance meets Defender of the Crown if you will. However, despite its clear genre antecedents, the game’s appeal lay neither in its asymmetrical battle sequences nor its deceptively complex resource management interface. No, the true appeal of UFO lay in its ability to create the impression of an ill-prepared and under-funded human bureaucracy struggling to cope with a catastrophic realignment of humanity’s perceived place in the universe.

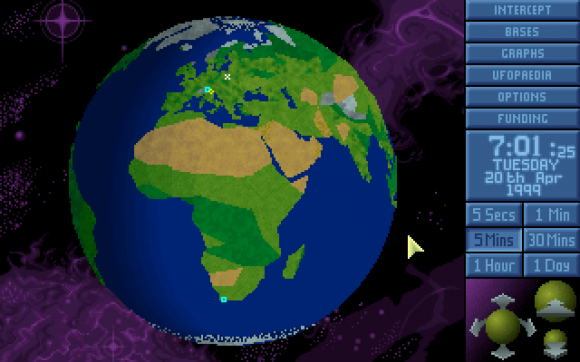

The tone is set by the game’s resource management system: built to resemble period software right down to the poorly-rendered spinning globe, the game’s outermost user interface adopted an almost corporate aesthetic. Like Captain Jean-Luc Picard’s upper-management meetings replete with beige office furniture and ferns, UFO looked like the type of software a military bureaucracy might have designed back in the mid-1990s: Here’s your pastel colour-scheme, here are your timers counting down to the next deadline, here are the faceless dolls representing your military personnel. It was all beautifully mundane and creaky, like the Gulf War running on Windows 95. Even the music was tastefully neutral and faintly reminiscent of what you might hear in the lift at a corporate headquarters. Here was an interface designed by a culture smugly certain that it could take anything the universe might throw at it.

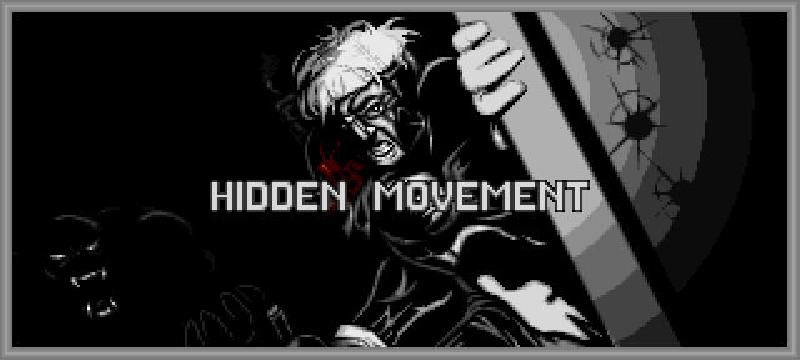

This illusion was artfully carried over into the early UFO encounters that deposited your soldiers in what appeared to be Midwestern agricultural land. Brilliantly, the designers decided to cloak much of this landscape in darkness meaning that initial rounds frequently saw your dudes painstakingly navigating their way around an abandoned farm complex as though part of some bizarre paramilitary re-imagining of Harvest Moon. Then, suddenly, the world would change: A glimpse of something moving in the darkness, a flash of light and suddenly you’re one man down while your heavy-weapons expert is firing rockets into corn fields. What the fuck happened? What was that? Where’s the tasteful pastel menu for ‘pull yourselves together and kill that fucking thing’?

Despite drawing on the same generic alien mythology that inspired such 90s staples as The X-Files, UFO’s aliens seemed utterly Other as their presence seemed completely out of place amidst the mundane certainties of the game’s backdrops and interfaces: Midwestern farms should not contain lurking snake people, suburban landscapes should not feature spinning metallic discs and 1990s resource management software is not designed to help humanity come to terms with its place in the universe. UFO is not about killing aliens and building bases, it is about learning that the world is a more complex place than you previously thought and adapting to life in that radically changing environment.

UFO conveys this impression of a world undergoing radical change by making use of a technique much beloved of generations of horror writers. In Nigel Kneale’s Quatermass and the Pit, a group of British scientists find an alien spacecraft buried beneath a London street and soon come to realise that humanity is descended from a group of aliens whose savagery accounts for many of the darker passages of human history. In H.P. Lovecraft’s At The Mountains of Madness, a similar group of scientists explore the Antarctic and discover traces of a civilisation that both predates and explains human existence. In both stories, the characters experience a terrifying sensation of slippage as the world they are familiar with dissolves to reveal a far more complex and terrifying reality than they could possibly have imagined.

UFO makes brilliant use of this technique by perpetually dragging us back and forth between the comfortingly smug pastel colours of our corporate resource management software and the reality of a world in which humans are no longer at the top of the food chain. Every time a Midwestern farm turns into a slaughterhouse and every time we return to the corporate interface we are reminded of how wrong we were to believe ourselves safe. Every time that corporate interface sounds an alarm or calmly informs us that we are running out of both money and soldiers, we are reminded of how ill prepared humanity was for this confrontation with the universal Other.

Humanity’s profound ignorance is further highlighted by the fact the bureaucracy does not simply research new weapons systems, it also researches the origins of the aliens in an effort to make sense of what is actually happening. Indeed, it is only once you work out who the aliens are and what it is that they are attempting to achieve that you begin to turn a corner and stop passively reacting to the aliens’ interventions on Earth.

The most impressive thing about UFO is the way that it captures what it’s like to be on the receiving end of a vast conspiracy. Play through the game with varying levels of competence and you will be struck by the fact that a gifted player can only ever slow down the alien invasion. You cannot break the aliens in an early battle or get the drop on them by pre-empting the game’s narrative… you can only deploy your soldiers, make the right decisions and hope that you learn fast enough to go on the offensive before it’s too late. Make the wrong decisions early on and the game will take you from tentative rural skirmishes to casualty-laden urban clusterfucks in a few short months but make the right decisions and you might get the chance to take the fight to the aliens before they drop a mothership on top of your home base. By connecting the speed of the invasion narrative to the competence of the player, the game manages to both give the player a sense of control over events, and make it clear to them that humanity is no longer in the historical driving seat. UFO is a game that is full of known unknowns but it’s always the unknown unknowns that get you in the end because nobody is ever completely ready to meet CompThulhu or for the suggestion that the player’s actions might well have nudged Humanity onto the same developmental track pursued by the aliens. This too plays into the game’s sense of slippage as the aliens do not just represent some catastrophic social upheaval, they also represent one of Humanity’s potential futures thereby suggesting that the player’s militaristic attempt to preserve the status quo may in fact be dooming Humanity to a future of inhuman belligerence.

The genius of UFO: Enemy Unknown lies neither in its game mechanics nor in its plotting but in its thematic depth and the way in which it uses mood and texture to capture what it is like to be lost, what it is like to find oneself, and what it is like to wonder what it is that one has become. My only regret is that the game’s recent remake (named XCOM: Enemy Unknown) completely fails to understand what made the original game so powerful.

Why the new XCOM is enjoyable fluff…

Aside from the fact that it is an X-Com game that is available on the current generation of consoles, the allure of XCOM lies chiefly in the fact that its combat system was designed in a world containing a relatively mature tactical RPG sub-genre. Thus, rather than a series of slow and frustrating tactical encounters featuring an array of faceless skill packages, XCOM offers a succession of engaging and well-paced skirmishes with enough tactical focus and cinematic panache to keep you entertained and interested through dozens of hours of play. The ability to personalise both the look and name of your troopers also gives your soldiers sufficient emotional substance to ensure that their loss is felt on a human level. Indeed, when I lost my most experienced Heavy, I did not grieve for his skills as much as I did for the fact that I had named him for the veteran science fiction critic and encyclopaedist John Clute. Frankly, I can live without an experienced Heavy for a few missions but the thought of a world without impenetrably over-written book reviews strikes me as almost immeasurably sad. Unfortunately, beyond these limited upgrades to the battle system, XCOM struggles to find a tone that is appropriate to the subject matter.

The problems begin with the tutorial mission. Rather than it taking place in the relatively benign environs of a Midwestern farm, my tutorial mission took place on the rain-slicked streets of Berlin. Right from the start, XCOM piles on the atmospherics with enough mood lighting and sinister music to make the eventual appearance of the aliens seem like something of an anti-climax. Far from being Otherworldly invaders, this first group of aliens seems perfectly at home in a world filled with long shadows and muscular military presences. Even more problematic is the fact that, because this is a tutorial mission taking place largely on rails, the aliens seem like a complete pushover thereby depriving them of menace as well as Otherness.

The biggest mistake that XCOM makes is opening the game on a note of panic and keeping it there for the entirety of its running time. XCOM attempts to recreate the original game’s mood of ill-preparedness but rather than allowing players to realise that proprietary corporate software packages will not save them, XCOM embeds this idea in the lugubrious architectural interface used to navigate between the bureaucracy’s different departments. Whereas the original X-Com headquarters spoke of corporate hubris that fell apart as the game progressed, the new XCOM base looks like something assembled as an afterthought. Evidently humanity was so ill prepared for an alien invasion that nobody thought to provide its multi-billion dollar paramilitary defence force with sufficient light bulbs. The game’s top-down approach to mood is also evident in the disastrous decision to lend each department a human face.

As well as being objectively less well designed than their original counterparts, the science and engineering interfaces have also acquired a pair of generic characters whose job it is to react emotionally to every bit of plot development. Thus, rather than calmly depositing news of humanity’s ultimate insignificance into your in-box, XCOM laboriously explains it to you in a cut scene imbued with all the emotional sophistication of a Michael Bay movie aimed solely at people with debilitating head injuries.

XCOM has little time for ambiguity or allowing its players to draw their own conclusions. Rather than allowing players to form their own ideas about what it is they are seeing, the game’s visuals scream ‘You’re fucked! This is really dangerous!’ in the player’s face and the screaming only stops when they eventually wander off to do something more intellectually satisfying such as rolling around on the floor making barnyard noises.

Much of the power of the original game lay in its unusual willingness to allow the players to formulate their own emotional reactions to the implications of the plot. The original UFO did not drive home humanity’s insignificance or spell out the idea that human civilisation might one day come to resemble that of the aliens… instead, the game placed this information in the player’s purple corporate in-box and allowed them to join up the dots in their own time. By allowing the player to happen upon these implications on their own terms and in the context of a bland corporate software interface, UFO imbued these revelations with real emotional power: these were not mere tactical details culled from an intelligence briefing, these were hard and uncomfortable truths about the world, truths that shattered the illusions of calm and certainty contained in those pastel colours.

By electing to have this information spoon-fed to the player by a pair of hysterical genre archetypes, XCOM not only denies players the chance to draw their own conclusions, it also does away with any pretence that an alien invasion might somehow be at odds with the world of the game. The original UFO aliens were cracks in the surface of reality, monstrously destabilising incursions into a world that humanity believed it understood. Conversely, the XCOM aliens are natives to a world that begins coiled in expectation of imminent alien invasion. Utterly at home in a world of underfunded paramilitary alien hunters and rain-slicked urban dystopias, XCOM’s aliens are nothing more than the generic bad guys from a moderately well realised tactical shooter.

To make matters even worse, XCOM’s writers have attempted to compensate for this emotional shortfall by reaching for ever-more purple prose including one grotesquely gothic interlude in which the acquisition of generic psychic powers is described as humanity peeking behind some sort of mystical veil. Needless to say, this top-down sense of awe is entirely absent from the practical deployment of psychic powers, which is presented as nothing more awe-inspiring than another option on the weapons menu. Apparently achieving enlightenment and oneness with the Godhead does 3 points of damage!

The more emotionally manipulative the game becomes, the more its attempts to evoke feelings of awe and terror seem ludicrous and ill conceived. Given that the game begins by situating us in a world poised on the brink of a massive alien invasion, why are we expected to be surprised when humanity winds up building its own UFO and finding a way to develop psychic powers? These are genre staples and this is a genre game; XCOM’sattempt to artificially imbue these staples with emotional energy is as absurd as a single-player military FPS that decides to talk about the horrors of war after the player has spent hundreds of hours machine-gunning Nazi soldiers and tea-bagging sinister Muslims.

In many ways, XCOM is an entirely decent and timely update of a classic game: Good to look at, rewarding to play and more than capable of capturing that sense of unease you once felt upon stepping into the carcass of a ruined UFO, it is a game that is entirely consistent with recent developments in AAA video game storytelling. The real problem is that the only insight gained by AAA game developers over the last ten years has been to transform everything into a boss fight.

Why Must All Games Be Nothing But Boss Fights?

One of the ways in which game developers get around a lack of memory is by re-using the same material over and over again in an effort to pad out a game’s lifespan. This is why the original Halo sends you hurtling across a series of landscapes only to then turn you around and send you hurtling back in the opposite direction. Back in the 70s, 80s and 90s, this type of recycling was particularly obvious as developers would just change a few colours and reuse the same enemies and backgrounds over and over again.

In an effort to stretch their material that little bit further and break up the monotony that comes from fighting the same things over and over again, game designers would often aggressively reframe one particular section as a boss fight. This process of reframing generally involved clearing the screen of all ‘normal’ enemies and changing the music to something more befitting a terrifying head-to-head confrontation. Even though all you were ever actually doing was fighting an enemy with a few extra hit points, these aesthetic tweaks not only cleansed the palate allowing you to go back to ‘normal’ fights without getting bored, they also seemed a lot more tense and important.

As time went by and the technological capacity of video games increased, game developers became increasingly skilled at using all manner of tricks to re-frame particular fight scenes. Taking their cues from Hollywood action movies, video game boss fights soon moved beyond different music and cleared screens to using cut-scenes and graphical flourishes to both whet players’ appetites going into a fight and punctuate the dramatic beats of the confrontation while it is taking place:

An excellent example of the former is the way in which Batman:Arkham Asylum has Croc repeatedly appear just out of the player’s reach. Every time the villain appears, the game slows down to emphasise his immense physical presence and create the expectation that taking down Croc will be almost impossible.

An equally useful example of the latter is the way in which JRPGs such as Final Fantasy VII would display lengthy animations each time the player unleashed a particular type of attack. The slowing of the game and the striking nature of the animations illustrates the growing competence of the characters and their capacity to unleash terrifying damage on those who oppose them.

Few developers understand the structural importance of boss fights better than Hideo Kojima. Shameless in its scene-setting histrionics and ruthless in its willingness to terminate an enjoyable section of play before it gets boring, Kojima’s Metal Gear Solid series has come to be seen as the bench-mark for cinematic video game storytelling. This development is rather interesting as while Kojima’s stories are invariably stylish and well-paced, their plots are invariably either intensely stupid or completely incoherent. In other words, while Kojima has mastered the narrative dark arts of emotional manipulation, his ability to come up with stories worth telling remains as limited as ever.

XCOM resembles the Metal Gear Solid series in so far as its approach to narrative is as totalitarian as it is melodramatic. Rather than trusting their material and their audience to find one another in an organic fashion, the writers of XCOM drive home every beat and every emotion as hard as they possibly can. Where the original UFO allowed players to uncover the disconnect between terrifying world and bland corporate office on their own terms, XCOM displays humanity’s precarious position in every colour scheme, every piece of text and every poorly performed and written cut-scene.

Games like XCOM are the product of a creative environment in which there is no room for subtlety or nuance. Like advertisers and political demagogues, AAA game designers are convinced that the only way of making the audience care is by reaching into their heads and forcing them to do so. Once upon a time, game designers used certain top-down narrative techniques to break up the monotony of fighting the same three enemies over and over again. Now, game designers use variations on these same manipulative techniques to wring emotional responses from the same old poorly written stories.

AAA game designers are now habitually returning to a well that has long since run dry. The basic problem is that if you create a calm game only to then occasionally shift to a more hysterical tone then those moments of hysteria will have real impact. However, if you create a hysterical game and them attempt to make the tone even more hysterical in an effort to grab the audience’s attention then chances are that all you will have is a ludicrous and inhuman mess. Rather than learning to tell stories filled with nuance and contrast, AAA game designers have spent the last ten years digging deeper and deeper wells in an effort to make their hysterical games seem even more hysterical! Much like the history of advertising, the history of mainstream video game narratives is one dominated by louder music, better visuals and ever-expanding production costs. Rather than telling stories that connect with us on a human level, AAA game designers have attempted to imbue their stories with the appearance of significance by turning everything into one enormous boss fight hence the increasing use of cut-scenes, quick time events and bosses that are too big to fit on the screen. You simply cannot make a mass-market console game that looks like the original UFO when people are making games that look like Bayonetta; the audience’s emotional palate has now become so desensitised that they would not be able to taste its delicate mix of narrative spices.

Much has been made of video games coming to rival Hollywood movies but given how terrible Hollywood movies can frequently be, I can’t help but see this as a bad thing. Games like Journey and works by Christine Love such as Analogue: A Hate Story and don’t take it personally, babe, it just ain’t your story are filled with ambiguity, insight and emotional intelligence but these games are now so far removed from the mainstream of gaming that they almost seem to be part of some secondary hobby (an impression accelerated by the near disappearance of mid-list titles). Some critics have been swift to seize on this disconnect and to champion the existence of ‘art house’ video gaming but the real danger here is not that intelligent games will cease to be made, it is that the narrative techniques used in intelligent games will entirely cease to appear in AAA titles. As a film lover, I am as capable of enjoying Transformers as I am L’Avventura but my true preference lies with the films that exist between these two truncated extremes, films like those created by Alfred Hitchcock, Stanley Kubrick, Howard Hawks and Claude Chabrol: works that combine the ability to craft a compelling narrative that forces me to care whilst allowing me enough room to draw my own conclusions about certain matters. By removing all nuance in favour of heavy-handed emotional manipulation, the developers of XCOM have effectively remade The French Connection as Bad Boys II.

[Jonathan McCalmont blogs at Ruthless Culture.]

Comments

25 responses to “XCOM is Not a Boss Fight”

[…] anything about video games but the awesome group blog Arcadian Rhythms were kind enough to host a little something I wrote about the stylistic differences between the original UFO: Enemy Unknown and its recent re-make […]

Huh.

I skipped all of the cutscenes I could and ignored pretty much any expositions I could (including the the cut away action moments in the turnbased sections) simply because I ignore them in most games due to them being terrible. As a result the crux of your argument about the heavy handed narrative delivery echoed through two terrible ciphers was completely lost on me.

For me, there was all of that little pop up telling me that each area was descending into panic while I sat in safety watching it happen, a creeping sense of dread coming upon me as the countries pulled funding.

At the time the tutorial made a lot of sense to me (the message being: get used to losing 75% of your team) but I can see what you mean by the fact that the starting state is panic. This mirrors the starting point I was at when I played XCOM: Apocalypse.

Still, interesting read, it sounds like I played the game 'wrong' and it ended up being a better experience for it.

Having listened to the podcast (great job on those BTW, really enjoying them) I think you engaged with the game's systems and found them to be a great improvement on those of the originals. I think that, by and large, they are a huge improvement as they take what was good in the original games and augment it with a decade's worth of familiarity with the tactical RPG sub-genre.

My complaint is really little more than an attempt to draw attention to the fact that the style of the game is actually a considerable step back from the style of the original. I think the style of the original accounted for a good deal of its charm and the remake's failure to either keep that style or improve upon it made the remake less impressive than it should really have been.

I have to admit that I never read UFO's interface as a piece of slick corporate software, but I love that interpretation. I think I saw it more as a slightly grungey 90s take on stuff like the dreadful 70s UFO TV series.

You've nailed it, though. UFO: Enemy Unknown was about atmosphere – ditto the brutal Terror From the Deep, which was the same game but drawing on Lovecraft and Wyndham rather than the 90s craze for conspiracies and alien abduction. The strategic metagame is peaceful, serene almost. The player is in control. I used to sit in fear, hoping that research and engineering projects would pop up their safe little completion notifications before another UFO appeared to smash my Interceptors and, should I succeed in actually shooting it down, blowing up another sixteen good men.

It's a relatively minor point but on the subject of humanity evolution possibly taking a course toward that of the invaders… well, X-COM Apocalypse opens with Alien/Human hybrids (Sectoids, the little "Gray" dudes) as recruit-able psionically-skilled soldiers, and towards the end of the game one of the final missions features a small group of the original Sectoids… who have themselves been taken as slaves by Apocalypse's invaders. Whether or not the Gollop brothers set out to achieve what you've outlined so compellingly above, they were certainly aware of certain ironies (or ironic opportunities).

As for the modern game: there are occasional tongue-in-cheek moments, specifically the autopsy scenes with their gory sprays of blood and the weapon range tests with the cardboard cut-outs of the original UFO alien graphics. But this does not extend into the narrative, for better or worse, and the tone is certainly driven by melodrama and pomp rather than genuine tension. Mechanically, I love the game. Narratively, it is simply adequate when not questioned.

But there is hope that we might see greater narrative sophistication in games. Spec Ops: The Line is a great recent example which AJ reviewed earlier in the year. I'm currently reading Brendan Keogh's 'Killing is Harmless' – an attempt at longform critical analysis of the game (a 50,000 word ebook). I hope to talk about that in the new year.

I'll look forward to your views on Killing is Harmless as I am curious to see what a 50,000 word piece on a single game actually looks like.

I'm happy to be corrected on the suggestion that the X-Com organisation might be setting humanity on a similar developmental path to the aliens as it has been a long time since I played the original games. I had Apocalypse on PC but I think my specs were not quite up to it and I moved over to Apple rather than upgrading so all I can remember was the hybrids and the fact that the X-Com agency does create a bunch of soldiers who look a lot like aliens come the end of the game. I always took the missions where you raid an alien base to be a sort of inversion of the early missions, recasting human soldiers as hostile Others in an alien landscape. I don't remember the games ever explicitly spelling out that humanity was becoming more like the aliens but I had assumed it was quite heavily implied if you paid attention :-)

Killing is Harmless is interesting but flawed. More on that later.

Apocalypse is a weird one when considered thematically; the endgame involves going to the home city of the inter-dimensional invaders and destroying crucial 'organs' (buildings) in turn. You can even kidnap their queen to improve your technology – literally abduct and experiment on her. It's rather fascistic in some ways, from simple hat tips and up (I think the city itself is named for a Judge Dredd megalopolis). The game also lets you behave like a thug and raid buildings within the city yourself.

The setting posits an Earth almost bereft of human life, literally a city under siege, and that mentality is going to produce a different response – a crueller and more suspicious attitude. I wonder what the Gallops would've done next if they'd retained creative control over the series?

A fascinating piece, even if (like Shaun) I didn't regard the UI aesthetic in that manner either. A very interesting perspective though.

I didn't play the original UFO until the mid 2000s on WinUAE (I never got hold of it on my Amiga 500 back in the day) and was so utterly enthralled by it that I got it for the PC to avoid the chronic load times. I stuck with it for a fair while but the interface got the better of me in the end and I ditched it. I haven't played the new XCOM though because I've been too busy with various other titles.

I can relate with your point about desensitising players with ever-increasing levels of DRAMA. It seems that AAA devs are trying to find a volume level higher than 11 all the time. It's bigger, it's better! Look dudes, there's none more loud than 11.

It wasn't until 1995 that Terror From the Deep revolutionised the X-COM UI by allowing soldiers to open doors before blundering through them directly into enemy fire. :)

Game designers have learned a lot from action movie directors but the lesson they really need to learn is that the sensation of pace and tone is largely relative. If you have everyone running around and exploding all the time, you don't have an exciting film… you have a hysterical film like Transformers.

In absolute terms, there's nothing higher than 11 but if you're at 3 for a couple of hours, 7 can feel like 105.

I think XCOM is a great game as long as nobody is speaking.

I played it in Ironman mode on Classic from the beginning and failed quite a few times before I beat it. In retrospect I think this was precisely the right way to go to get maximum enjoyment out of it. For me, anyway. I didn't even mind the lame end game that much as I was just happy to have finally won.

I rather wish I had done the same (well, with Classic, I mean – bugger Ironman). I started out that way but subsequently switched to Normal, which went too far the other way. I can only imagine what a cakewalk Casual must be.

One way in which XCOM doesn't stray into melodrama is when your soldiers take a shot. Each animation plays out just long enough to keep you on the edge of your seat, hoping that this shot pay off – even more so at a critical juncture in a firefight. Whereas in UFO it was pretty standard to inch forwards until one soldier spotted an alien, then have everyone with line of sight blindfire at it in the hopes of scoring a kill without exposing anyone else to reaction fire.

First of all:

You make a great point: UFO communicates through it's aesthetics a disconnect between the narrative and the interface of the game, a disconnect that parallels the disconnect between how man views himself and what man actually is, at least within the context of the game.

Like, yeah, sure. That's a great point, and hammering the disconnect home gives a sense of realism to the game, as well as a larger than life perspective on the work in and of the corporate and military sectors. Yes. This is good. Having not actually played UFO, I don't have the faintest clue about how well the disconnect is executed or whether I would attribute it to clever design like you do, but sure. I have learned something here today.

But then…you want XCOM to make the same point again? Or at least a similar one? Like, the intertextuality with the corporate resource management software you mentioned is clear, but that doesn't exist anymore. So. You think you could do a microsoft word ribbon, icons, and an excell tab with spreadsheets? Really? Or do you perhaps want to mimic an Ubuntu or other Linux workstations interface, like Uplink does it?

The aspect of XCOM most alike what you describe is the ufo takedown screen; you launch an interceptor, you have a number of specially developed hand-crafted packages you can launch, and you can abort. Whether you have access to these things depends on whether you sold your alien tech on the grey market, or you spent funds putting them together. You can also abort the mission, and send up another bird to finish the job. You're not the pilot, you're just his CO, and you decide these things through a piece of software that looks pretty much exactly like what you want. But it's better yet.

I had a situation where I was upgrading the arms on an interceptor, and a ufo appears over the region. Only have that one available, but it's done rearming in 2 hours, so I nudge the speed forward and then I wait most of the last hour manually. At 5:36 AM, it is done rearming, but now it needs to refuel, and that apparently takes an hour before it's ready at 6:36 AM I launch it, barely within the window where the UFP would otherwise escape, and perhaps take down my satelite over the area. All of this gameplay happen within the interface of the game, and I'll let you know right now, apart from thoroughly impressing me with how well made it was, yes, I did feel the exact disconnect you ascribe to the first UFO, but it all still worked.

So. I'd argue that firaxis did try to design things in a fashion fitting with modern military resource management, but most of the game just isn't amenable to that, and they did something else for those parts.

Secondly, your focus is all wrong. You look at the naration and the aesthetics of the interface, and then you go on a tirade about boss fights and hysteria. Why aren't you focusing on the gameplay? And then…I discover, in the comments, that you played the game on normal, with savescumming allowed. That you admit this was probably a mistake. No shit.

If you were playing the original game, I'm going to go ahead and guess you've played games for the past 20 years. You're not the demographic normal is targeted at. Further, maybe you're impatient and you like easy games, and you don't want to spend the time to appreciate difficult ones, or you might get frustrated and not enjoy it. Ok. Fair enough, I respect that, but then this piece is like taking a comic book geek to visit the van gogh museum in amsterdam, and asking what he thinks. He might do a perfectly amenable job at analyzing composition and choice of colour, he might even compose a nice response, but there's a massive amount of stuff he just won't get.

This is how I feel about your piece now. You wrote it this way because you didn't know any better. You focused on narrative and narrative structure – and you had some good insights – but you class this game as an undaring gaming that doesn't have pacing, that is digging a hysteria pit. Little do you know that the game has excellent pacing on the higher difficulty levels. The narrative doesn't seem hysteric because if you lose your best squad, you likely lose the game and the 10+ hours you put in (I've lost a 15 hour game myself). There's this whole dimension to the game, and you don't even see it. And this is clearly the connoseur version of the game. This is the version that has deeper meaning, that gives you something. And you're not even interested.

Xcom actually speaks to you through the way the gameplay is designed, but if you don't listen to that, yeah, ok. Then your analysis is probably alright. But there's so much more to it. And you know, I'd even argue that your negative attitude that games aren't progressing, or they're losing their language – no. You're wrong. They're finally starting to develop a language that is spoken through play and rules, rather than narrative and other superficial things that aren't even at the core of the experience.

I'll let Jonathan respond to your points himself, but I should note that the person who "played the game on normal, with savescumming allowed" was me.

Tangentially, I didn't activate Iron Man because I don't trust the UI or bugs to not fuck me over. It is possible to simply make a decision to not savescum. XCOM is a game that allows this.

You might enjoy our podcast on XCOM – several of us spent a good hour talking over the game.

This is true; I was assuming a bit about the playstyle of a non-iron-man player. Also, uh, apparently I mixed you two up, sorry.

I think Mr. McCalmont was using XCOM as a springboard to address a larger point. I'm not sure that XCOM is the most natural example to use, but the point is valid.

(Though when he says: "As well as being objectively less well designed than their original counterparts, the science and engineering interfaces…" he seems to be using the word 'objectively' in a sense unfamiliar to me.)

XCOM does have very poor presentation, though; most of the cutscenes are just embarrassing. The doctors do love to talk, and almost everything they say is inane. The sorry excuse for a lieutenant isn't any better: "Let me get this straight. Are you seriously suggesting we should attempt to gather intelligence on our unknown enemies?"

And XCOM is, I think, poorly paced. It cranks up way too fast, which is why I briefly attempted to play it on Normal. Unfortunately, the pace was the same, but it was too easy to be fun, so I abandoned that game and returned to banging my head against the wall on Classic.

But I really dig the gameplay. It's fairly clear this is an offering from Sid's company, and the devs seem to have taken it to heart that a game is a series of interesting decisions.

Yeah, I think you're right that he _was_ using it as a springboard. Which would be fine, except it's a terrible example to start off of, and that kindof condemns the larger issue he's trying to tackle as well.

His analysis of UFO has this little nugget, for instance:

"Play through the game with varying levels of competence and you will be struck by the fact that a gifted player can only ever slow down the alien invasion."

It illustrates that he has either read about gifted players and newbies playing UFO, or he has spent a lot of time with the gameplay. There's a whole paragraph dedicated to what the gameplay of UFO says about humanity, and how it has worth.

There is no such paragraph in the XCOM subsection. The only point where he delves into the gameplay is when he decides to discuss the implication of naming soldiers. That's it. I have nothing to go on, no idea how much he's actually tinkered with and played the game in various ways, no idea how much he's tried to discover what the game system says. I only know that I think the game system says a lot, that it has meaning, just as he found the game system in UFO has meaning.

And he has this quote in the final section on bossfights:

"Games like XCOM are the product of a creative environment in which there is no room for subtlety or nuance"

Springboard or not, when there's no indepth analysis of what the gameplay of the game says, then that 'no room for subtlety or nuance' bit makes me think he didn't actually pay attention to the subtlety and nuance that's right there in the game system itself; and if he didn't, his whole point is moot, because then he's looking in the wrong place for subtlety and nuance.

Yeah, XCOM doesn't pretend to be grade A end of the world writing. It pretends to be Armageddon, or maybe 'The Core' in terms of its narrative. It does this, because all of that is just unimportant fluff anyway, and it's terribly hard to get right (it's really outside the means of most game studios to do); if a game is going to affect you better than a movie (a format where narrative and visuals are all there is), it must focus on what it says as a game.

That's what game studios are good at, and that's the vastly most important bit anyway.

So yeah, I don't mind that there's a critique of the static narrative elements; that's fine if it's an addendum to an analysis of the game as a system of rules and interactions. What I mind is that, apparently, a claim is made that the game studio has no room for subtle expression, without just some kind of a gameplay analysis to back this up.

Have to say, that I agree with a lot of both points being made. Jonathan's points about bombast are a good point, there is a fair bit in the current XCom that I completely missed (I recently revisited it due to this article) partly because I turned most of it off and partly because I skipped all the cut scenes.

I think it is telling that I ignored most of it and even found the game to be tremendously muted but this is only because of most of the rest of the rubbish out there right now (Mass Effect 3, Far Cry 3 any of the Assassin's Creed games) that makes XCom's delivery look pale by contrast.

I would have liked it if Jonathan could have made a few more nods to what I feel the game gets right – the voice acting of the troops is suitably indifferent, the way the game goes from routine to fucked up in about two seconds flat with the wrong planning being two notable moments.

And I definitely agree that there are more egregious examples of hyperbole out there. The Syndicate remake, as fun as it is, is an example of misunderstanding the core conceit of the original game (I don't blame Star breeze – the developers – for this) and some of the blown out nonsense I have sat through in the last year truly makes me sad.

My only arguments against what you are saying specifically are the following – if the cutscenes are junk and only on a level of the Aerosmith/Bruce Willis gash then why are they there at all? Firaxis must have wanted them, which is a poor decision in itself but now they have released DLC that is narrative focused… When they announced that I was a little flabbergasted as it was the direct opposite of all I that enjoyed in XCom (and I really enjoyed it) this suggests to me that they don't want you to ignore those cutscenes.

Also, all they would have needed to do wa watch the control booth sections in 28 Weeks Later and the whole of Contagion to be able to nail the story.

Anyway I liked both the article and your responses. It is nice to read articulate and well composed responses, I feel like those are far and few between. Thanks for taking the time to write.

To be honest with you, I'm not sure that game mechanics are a particularly expressive medium when it comes to emotional nuance.

A game with an even difficulty curve provides a steady drip-feed of endorphins with occasional spikes and troughs to break up the monotony. Games with less even difficulty curves move you from air-punching triumph to incandescent rage-quitting with very little in-between. At their best, game mechanics are pleasurable and rewarding and that's not a particularly interesting palate when it comes to painting emotional vistas.

I can see that you're coming from a place that says that writing about games MUST involve writing about mechanics but a) I don't think that's particularly germane to the point I was making (i.e. that AAA video games are tonally bombastic and don't need to be) and b) I don't think there's only one level on which one can engage with games.

If you want my opinion about the mechanics I'd say that, bugs not withstanding, it's a reasonable though hardly ground-breaking update of the old system that draws heavily on a decade in which tactical RPGs have become a genre in their own right. I would have *liked* a bit more room for specialisation in the career progressions. For example, while the skill choices contained implicit tactical dilemmas (i.e. Heavies evolving into either area-effect damage dealers OR area-control technicians who soften up groups of aliens while the other soldiers do the killing), a Vandal Hearts-style branching careers system would have made those choices a good deal more fun and consequential and might even have encouraged players to think more about which particular soldier did which particular job.

I have an opinion about the mechanics but I'm not sure that opinion was relevant to what I was trying to say :-)

Good points that I agree with except for the mechanics argument.

For me mechanics are like sentence structures. Depending on how they are implemented can greatly change the mood and emotions of the audience.

An example would be things like Spelunky with its whip. The whip in the beginning is your main weapon and has a block-length (a block being a square of earth in the game) of reach forward and about half a block-length at the back during the wind up. This is a very intentional choice as it would have been easy to give him an all powerful Castlevania whip with the same sort of range and rhythm. The more you play the game the more nuance to this mechanic you start to appreciate but at first you feel woefully unprepared and alone and this piddling whip accentuates that. The fact that the developer then chose to make it hurt but not damage co-players adds more elements to this. Your one recourse to save yourself can actually be the death of your teammates as they get sent spiraling into a pit by an attack you meant for a bat or snake.

As your skill grows though, and you learn of other methods to defeat or completely avoid enemies, the whip mishaps or ineffectiveness actually becomes a source of hilarity. The more you explore and grow your feelings towards that mechanic also grow.

I am going off on a tangent but I think that mechanics are the purest form of evoking emotions in games.

I think Xcom is a singluarly bad example to argue the limited range of emotions gameplay can evoke. Did the Hidden Movement portion never make you feel apprehensive? Nervous? Terrified even? Sending your people out into the dark or through a doorway only ever evoked feelings ranging from anger to pleasure?

Of course, when I talk about gameplay I mean something broader than naked mechanics. To me, it means the experience of playing the game and bleeds inseparably into some narrative and presentation elements and buying into the game premise. Of course, this is hardly an area with established terminology.

That's exactly the reason I wouldn't Iron Man XCOM, just in case there were bugs (I recall hearing about plenty of those on release). I'd go 'soft' Iron Man instead ie. restrain myself from savescumming. I don't recall the original X-COM having an Iron Man mode though…

From what I've read the original X-COM actually had a bug whereby the unpatched (fan-patched!) version would reset the difficulty to the minimum difficulty level after the first tactical mission. Yep, old games were totes more difficult!

(The joke goes that Terror From the Deep had the same bug but in the other direction.)

Not to mention TFTD was rendered unwinnable if you did things in the wrong order… didn't know that when I first played it, which is why I've never completed it. Got a little burned out doing a mission after mission wondering what the trigger for the final mission was.

I've played XCOM almost exclusively in Iron Man mode and haven't run into any show stoppers. I might have lost a few people to UI-related mishaps early on, but I think that was mostly me not paying attention.

There's a bug in the last mission whereby aliens can fall off the map and become impossible to kill, meaning that the trigger for the doors opening never happens. I can't exactly recall what I read about this last year but I think that Iron Man allows you to start the mission again from the beginning if all of your soldiers are killed… but if you've no way to engineer the death of your entire team (e.g. all the aliens you can reach are dead and you have no explosives) then you're fucked, and it's back to the start of the game with you. I ran into people complaining about this very problem when I encountered it in my (fortunately) non-Iron Man game.

I've encountered numerous nonsensical UI related deaths during my Ironman playthrough and I think I talked about a few more issues in the podcast. I want to play on Ironman again but those bugs made me so angry the first time.